Noise often impacts visitors’ experiences

Listen to the call of the wild and you might not hear what you expect.

Leaves and commercial jets rustle in the wind. Water and motorboats rush through the streams. Birds and cars make their presence known to their surroundings.

In a 1998 survey conducted by the National Park Service, 72 percent of visitors stated that one of the most important reasons for having national parks is to provide opportunities to experience the natural quiet and sounds of nature. Yet, visitors are often greeted with more than what they had expected.

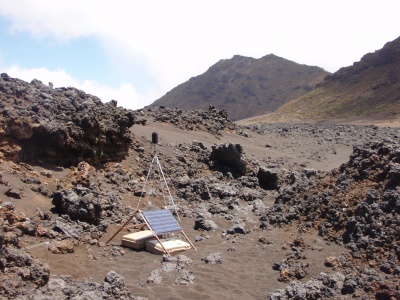

|

Soundscape inventory is taken using acoustical monitoring equipment in Hawaii’s Haleakala National Park (Photo by Damon Joyce, courtesy of the National Park Service). |

“When you get out in the backcountry area, people do not want to hear cell phones ringing or their boom box on,” said Vicki McCusker, a planner for the Natural Sounds Program Unit of the National Park Service

The natural ambience is being threatened by human-generated sound. Although aircraft overflights are often considered the major offender, motorboats, cars, snowmobiles as well as loud music are frequently deemed as sources of the noise pollution in parks.

“They are really not that loud,” said Jared Withers, a physical scientist at Denali National Park in Alaska. “They seem very apparent because it is so quiet otherwise. The impact really comes from the frequency of the interruptions.”

Biscayne National Park in South Florida is the largest marine park in the system and boat usage is high. Park Ranger Astrid Goderich recognized that, at “concentrated levels,” the noise becomes a problem.

Like the animals and natural environment, the soundscape at American national parks is seen as valuable resource that requires protection under the NPS mission.

Because it is considered an essential resource to animals and humans alike, disruptions have consequently led to adverse impacts on them both.

In recent years, there has been an acknowledgement of the effects that human-generated noise has produced on wild animals and their way of life. Although the intensity varies among species, there are studies being carried out in order to further our understanding of this problem.

| Each Columbus Day Weekend, hundreds of boats gather off of Elliott Key in Biscayne National Park (Photo by Gary Breman, courtesy of the National Park Service). |

|

Human-caused sounds affect the way animals communicate and this cascades into many problems, said McCusker. The introduction of loud noise leads to complications in predator-prey relationships, where one cannot hear the other. Stress levels in animals have also been seen to increase when exposed to constant sources of noise.

Negative repercussions specifically in aquatic life have also been identified.

Recreational boating and the movement of the propellers in the water are seen as major problems. When the propeller moves in the water, it creates air space that eventually moves to the surface and causes the water column below to collapse.

Multiple exposures to this, Vogel said, have been linked to hearing loss for dolphins and manatees. With this decrease in perception, chances for survival are slim and this ultimately results in increased mortality.

Sound pollution is seen as a problem with visitors of national parks as well. Its impact on human beings goes beyond annoyance.

“Noise causes stress,” said Ron Lai, after hearing a boat docking in Biscayne National Park. A native New Yorker, Lai has visited more than 50 national parks and appreciates the quiet.

McCusker described how studies are being conducted in order to get a better idea not only on the irritation of noise, but rather the benefits of natural sounds. She mentions the days following Sept. 11, 2001. With no planes flying, numbers of people commented on the quiet. They did not realize the magnitude of the noise that humans contribute to their surroundings.

|

A cutthroat trout leaping at LeHardy Rapids in Yellowstone National Park (Photo courtesy of the National Park Service). |

Following the mid-air collision in 1986 over the Grand Canyon, the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) stepped in. As the policy for overflights came under review, the NPS and FAA also took the opportunity to manage the noise they were generating.

In efforts to reverse the trend of increasing noise in parks, the Natural Sounds Program was established in 2000 as a unit of the National Park Service.

A lot of what the Natural Sounds Program works towards is generating a baseline for the natural ambience. If parks want to be restored to their natural soundscape, they have to determine what “natural” means. This is achieved by conducting long-term acoustic monitoring by continuous recording of specific areas.

When processing the recordings, they play them back and look for signals that indicate patterns. After observing the frequencies and removing the human-caused sounds, you are left with the natural ambience of the environment.

Once the baseline is established it is used to determine the condition of parks as well as dictate policies that need to be implemented or changed within them. Parks have already been seen making these adjustments.

With the passage of the National Park Air Tour Management Act in 2000, the FAA has been working with NPS in efforts to create air tour management plans for each park. McCusker estimated that there are 50 to 80 parks in need of one.

Grand Canyon National Park in Arizona was the first to be targeted. Park ranger and spokesperson Maureen Oltrogge described the installation of flight corridors above the canyon in order to mitigate the noise. It is a move that she said will reduce the concentration of overflights and allow people to better hear the “natural sounds and not the ones we have created.”

| Backcountry hikers travel to Denali National Park to escape the noise of urban areas and experience the natural ambiance (Photo courtesy of the National Park Service). |

|

Yellowstone National Park in Montana has addressed the issue with snowmobiles in the wintertime by prohibiting their private use. Operation is limited to those with a contracted guide company, which defines the numbers in use. This along with the usage of more quiet snowmobiles has led to a decrease in noise pollution.

Yet for some parks, policy changes are not all feasible.

In Biscayne National Park, reducing boat usage currently does not appear to be an option. The park is in an expanding urban area and just south of greater Miami.

“It is part of our soundscape,” said Goderich. Because most places are only accessible by boat, “[hearing] a boat going by in a park that is 95 percent water makes sense.”

Likewise, in the middle of the vast Alaskan wilderness, small aircraft are deemed more necessary for daily life and are thus given more rights. As a result, Denali National Park is not under the jurisdiction of the Air Tour Management Act and has been allowed to devise a plan specific to their park.

With the obstacles they face, park officials working with soundscape preservation still remain optimistic in completely restoring the natural ambience of parks.

“Complete restoration involves changes in people’s behavior, technology” and cooperation from agencies outside the park service, said McCusker.

Withers estimates that the natural ambience could be restored within 100 years.

“With technological improvements the opportunity may be there,” he said. “In the long term, I think it is possible, but on short term we’ll be searching for a compromise.”

|

The tranquility and solitude of Grand Canyon National Park has been threatened by their frequent overflights (Photo courtesy of the National Park Service). |

Although there is much speculation on how to go about the preservation of the soundscape, most agree that the value of undisrupted sounds of nature goes unparalleled.

Withers believes that national parks provide the opportunity to experience tranquility and solitude.

“People in the urban world forget what it is actually like,” he said. “It is the most important thing the park can offer.”

REPRESENTATIVE SOUND LEVELS AT NATIONAL PARKS

|

Sound |

dBA |

|

Threshold of human hearing |

0 |

|

Volcano crater – Haleakala National Park |

10 |

|

Leaves rustling – Canyonlands National Park |

20 |

|

Crickets (5 m) – Zion National Park |

40 |

|

Suburbs – Night |

45 |

|

Suburbs – Day |

55 |

|

Conversational Speech (5 m) – Whitman Mission National Historical Site |

60 |

|

Snowcoach (30 m) – Yellowstone National Park |

80 |

|

Military jet (120 m) – Yukon-Charley Rivers National Park |

120 |

Source: National Park Service.

Comments are Closed