Terrorism becomes concern for parks

As the saying often goes, “Everything changed on Sept. 11.”

But truly, much did change that day, most of it associated with security protocols across the country, and around the world. While the National Park Service has fought to keep up, one aspect of its crime fighting arm has fought to stay out of the red.

According to the National Park Service (NPS), there are almost a half-billion visits a year. Any one of those half-billion visitors could have intentions beyond enjoying the sights.

When individuals think of terrorist threats, their thoughts don’t immediately go to the national parks. Why would terrorists or other evil-doers want to blow up some trees?

|

A visitor looks out on the National Mall from the Lincoln Memorial, with the Washington Monument and U.S. Capitol Building in view. All three are under the supervision of the National Park Service and the U.S. Park Police (Photo courtesy of the National Park Service). |

But the NPS just doesn’t protect canyons or redwoods. It also maintains and protects most of the nation’s historic landmarks, including the iconic Washington Monument, Independence Hall and the Statue of Liberty.

The U.S. Dept. of the Interior, the cabinet-level department charged with operating the national parks, has two different types of personnel to deal with security: the park rangers and the park police.

Park rangers are that familiar group who wear the brown uniforms and serve in parks across the country. While they are famous for providing directions or tours for visitors, acting as an ambassador to the visitors, some rangers have added powers and duties and act as a police force at the park for which they are assigned.

Their protection duties range from the simple (keeping gates closed and visitors out of unauthorized areas), to the intricate (acting as the primary police force for the region and operating military style counter-drug operations).

| A park ranger on boat patrol. Rangers lead tours, but also help parks in more rural areas (Photo courtesy of the National Park Service). |  |

Although lesser known than the rangers, the U.S. Park Police is the group traditionally associated with crime fighting when someone thinks of the parks. The oldest uniformed law enforcement agency in the United States, the USPP have been in operation since 1791.

Originally known as the Park Watchmen and charged with guarding the White House, the USPP maintain security at park locations primarily in the Washington, D.C., New York and San Francisco areas.

USPP mainly cover historical sites and are the most visible anti-terrorism force in and around the nation’s sensitive sites. They have an aerial fleet and a mounted patrol and are in charge of security at large-scale events in the D.C. area, such as inaugurations, presidential funerals and large protests on the National Mall.

“We deal with urban areas. More rural areas are better served by the park rangers,” said Sgt. Robert Lachance, spokesman for the USPP. “Of course, we would call each other for help. The rangers call us for help with events at their sites and we call them in for events like the inauguration and protests.”

|

Eagle 1 is part of the U.S.Park Police’s aerial fleet. Eagle 1 saved five people from the frozen waters of the Potomac River after Air Florida Flight 90 crashed on Jan. 13, 1982 (Photo courtesy of the U.S. Park Police). |

The NPS does not release itemized security costs. Doing so is a security measure in itself. But some conclusions can be drawn from the USPP’s budget expenditures for over the past eight years.

In 1999, the USPP had a budget of $54.4 million. In 2002, the year following the attacks in New York, Washington, D.C., and Pennsylvania, spending increased to $65.2 million.

In President Bush’s most recent budget proposal, a total of $88.1 million is sought for the police. If approved, it would be a 62 percent increase in a span of nine years.

“Obviously, 9/11 changed everything. It made us focus more on terrorism” said Lachance. “But the USPP has always taken threats of terrorism very seriously, even before 9/11.”

The NPS rarely announces what security procedures are implemented; again, doing so might compromise the very system it is trying to bolster. However, the NPS has sought to ease the worries of those who may fear an attack and does announce when some large-scale security improvements are made.

Despite the national scope of their coverage, the USPP don’t work incredibly close to the Department of Homeland Security. They do receive alerts, plan large-scale security details and participate in workgroups like the Interagency Airspace Protection Working Group, designed to bring different groups together to collaborate on airspace security issues, but that’s about as much as they really do hand-in-hand with DHS.

“We really function like a regular police force,” said Lachance. “We deal with our area.”

One announcement made to the public after the attacks was the immediate accessibility of $30 million worth of discretionary funds to be used by the parks to beef up security. According to the NPS, $15 million was used to purchase new equipment and $15 million was used to hire and train new personnel.

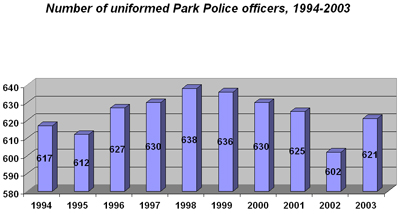

Funding has been an issue for the parks in many different areas and security is no exception. While USPP funding has increased since 1999, the number of officers in uniform has actually decreased. In 1999, the force had 636 officers in uniform, the most it has had dating back to the 1980s.

In 2002, the number had fallen to 602. Now, in a report published by the Public Employees for Environmental Responsibility (PEER), the force has only 587 officers on staff.

According to a published report by the USPP chapter of the Fraternal Order of Police, the funding situation has become dire. Officers have made repairs to vehicles without the help of the USPP. Rations for horses have been cut in half due to “grain shortages.” One canine handler even had to pay for kenneling out of pocket.

|

A graph showing the changes in the number of officers on the force from 1993 to 2004 (Source: U.S. Park Police). |

According to a study by the National Parks Conservation Association, a nonprofit group based in Washington that is focused on conserving and protecting the parks, the parks need about $600 million more, a 33 percent increase in funding, to operate at the level it should. The same study states that about $50 million of that shortfall stems from duties related to homeland security at the so-called “icons.”

The low staffing and lack of resources has lowered moral among USPP members. According to a survey compiled by the USPP Chapter of the Fraternal Order of Police, in which 179 of the approximately 400 line officers (those ranked below sergeant), revealed some worrying feelings shared among the officers whose job it is to protect this nation’s landmarks and the people who visit them.

According to the survey, released in January 2007:

- 94 percent of officers do not feel “the current staffing levels at your work site are safe.”

- 99 percent of officers do not believe that U.S. Park Police leadership is “doing the best they can to protect the public”

- 96 percent do not feel they “have the needed equipment to carry out your duties in case of a terrorist attack.”

- 85 percent do not “think that our ‘icons’ are as safe as they could be”

- 98 percent lack confidence in the current Chief of the Park Police Dwight E. Pettiford and 95 percent lack confidence in the “command staff”

| A U.S.Park Police officer on motorcycle patrol at the Washington Monument (Photo courtesy of the U.S. Park Police). |  |

Control over the park police has become a battle in recent years, as former Chief Teresa Chambers was relieved of her duties in July 2004 after speaking to the media on her department’s perceived under funding. Chambers sued the Park Police for her job and her case is still pending in the U.S. Court of Appeals.

On Nov. 28, 2003, Chambers wrote a budget memo that showed how large the deficit funding issue had become.

“My professional judgment, based upon 27 years of police service, six years as chief of police and countless interactions with police professionals across the country, is that we are at a staffing and resource crisis in the United States Park Police,” Chambers said to The Washington Post at the time. “A crisis that, if allowed to continue, will almost surely result in the loss of life or the destruction of one of our nation’s most valued symbols of freedom and democracy.”

|

Teresa Chambers, former chief of the U.S. Park Police. Chambers was fired after commenting to The Washington Post about the force’s budgetary shortfall (Photo courtesy of Public Employees for Environmental Responsibility). |

Chambers spoke to The Washington Post about her concern a week before the memo was released and the article on the subject appeared on Dec. 2. Three days later, the chief was on administrative leave.

According to NPS policy, officials are prohibited from public comment about budget discussions. But Chambers believes that her tough comments towards the administration’s funding provoked her removal.

“The American people should be afraid of this kind of silencing of professionals in any field,” Chambers told CNN after her firing. “We should be very concerned as American citizens that people who are experts in their field either can’t speak up, or, as we’re seeing now in the parks service, won’t speak up.”

Chambers’ fight against the NPS continues and so do the questions about funding. No matter the money involved, the USPP officers still suit up and do their best to defend some of the world’s most famous landmarks.

“We’re one small part of a large puzzle and we have to work within the limits of what we’re given,” Lachance said. “But we do everything we can to provide a safe and enjoyable experience to our visitors.”

Comments are Closed