Illegal immigrants bring problems to parks

The Cold War was over, but a new war started that the country is still fighting today. And it is not in the Middle East.

In the mid-1990s, America began its “war on drugs” and curbed illegal immigration along Mexican-American border cities. This took the dogged and desperate around American checkpoints and into the Arizona, New Mexico and Texas deserts that were thought to be so severe that they policed themselves.

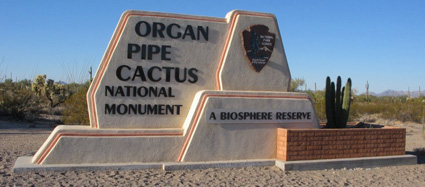

| Organ Pipe Cactus National Monument in Ajo, Ariz. (Photo by Steve Garufi). |  |

Tightening the borders had a direct impact on U.S. national parks that neighbor Mexico. The park system didn’t have a defensive strategy to curb eager drug runners and desperate alien workers who saw vast unprotected lands as their entrance to the United States.

“No one was expecting it to be as bad as it was,” said Andy Fisher, chief of Interpretation at Organ Pipe Cactus National Monument in Arizona. “It was definitely more a reaction than being ready for it.”

Currently the situation has park rangers facing dangerous situations, ecological systems being ruined, and visitors being limited access to areas of the park.

Organ Pipe lies at the forefront of the border security issue. It includes 30 miles of open border between the United States and Mexico.

According to National Park Service research, during peak months of migration, around 1,000 illegal immigrants could transit Organ Pipe in a 24-hour period. During the year 2007, park rangers seized more than 14,000 pounds of marijuana smuggled through the park and arrested 500 undocumented aliens.

In response to the dangers created by drug runners and illegal immigrants, the U.S. Park Rangers Lodge of the Fraternal Order of Police named the 330,000 acre Organ Pipe National Monument the most dangerous national park for law enforcement in 2002 and 2003. The cited reasons were illegal immigration, drug running, and low ranger staffing.

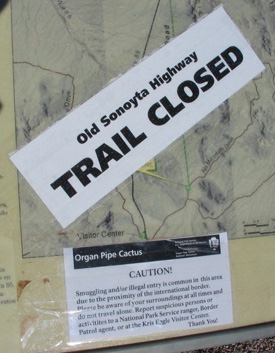

| Park rangers have closed 60 percent of Organ Pipe Cactus National Monument to visitors, including the Old Sonoyta Highway, due to drug smuggling and illegal migration (Photo by Steve Garufi). |

|

“We put the list out to show that rangers are being assaulted at a high rate,” said George Durkee, director of the U.S. Park Rangers Lodge based in Twain Harte, Ca. “We were looking to draw attention to our issue. The fear of speaking freely, inspired by the current administration has trickled down to all levels of government.”

The list proved too accurate.

In August of 2002, a stolen SUV with gun-wielding men drove a common route through a flimsy fence that separated Mexico from Arizona. Organ Pipe Park Ranger Kris Eggle was shot and killed while assisting U.S. Customs and Border Protection in apprehending the men who were suspected in drug-related murders.

The death of the 28-year-old started a movement to protect the park and those who serve it from the dangers of the border.

“The people who loved Kris had to do more,” said Fisher. “Almost everyone who came on to law enforcement here….came to fix the issue that had killed Kris.”

Immediately, the first step was to increase the number of law enforcement rangers in Organ Pipe.

“After Eggle was killed there was a huge outcry that we need more rangers,” said Durkee. “It hit a nerve in Washington, D.C. They said we have a problem here. The ranger had no support and no back up. The potential was there for the tragedy that occurred.”

The buildup in law enforcement officers was only temporary after the death.

“Are we at where we’re were suppose to be? Definitely not,” said Organ Pipe Chief Ranger Dane Tantay. “But we’ve improved through support from the regional and Washington office.”

|

U.S. Border Patrol vehicles parked on the Ajo mountain loop inside Organ Pipe (Photo by Steve Garufi). |

Tantay refused to release current ranger staffing numbers citing officer safety concerns.

“The answer to officer safety at Organ Pipe is numbers,” said retired ranger and former National Park Ranger Fraternal Order President Randal Kendrick. “You need to count on immediate back up rather than a number of hours.”

To preserve sensitive desert ecosystems and increase officer safety, an $18 million, 23-mile vehicle barrier was constructed out of twisted railroad ties soon after the Eggle incident. The barrier prevents vehicles from running unchecked across a drug smuggler-made desert highway.

“They [drug runners] use vehicles as weapons,” said Jesus Rodriguez, spokesman for the U.S. Border Patrol, Tucson Sector. “If you equate vehicles as weapons, it takes a weapon out of their hands.”

The barrier has essentially stopped all vehicles from crossing the desert illegally while still allowing the natural migration of animals.

“The vehicle barrier has been extremely effective,” said Organ Pipe operations supervisor, Ranger Hunter Bailey. “Prior to the vehicle barrier there was a lot of road traffic and destruction of vegetation from people cutting down trees to create roads.”

Although there are still the occasional breaches of the vehicle barrier that requires immediate interdiction by Border Patrol and park rangers.The vehicle barrier was built intentionally with the idea of limited harm to the natural ecosystem while keeping the park safe. But now 5.2 miles of mesh fencing will be placed in the park to deter pedestrian immigrants near Lukeville, a border city within the southern boundary of the park.

| High tech virtual fencing proposed for Organ Pipe that uses radar and cameras not physical barriers to prevent illegal immigration (Photo by James Tourtellotte, U.S. Customs and Border Protection). |

|

This fence has caused some tension between governmental agencies in favor of a fence and environmentalists who believe the fence will disrupt a natural migratory flow of animals, including 39 endangered species believed to be already affected by Border Patrol operations.

“No matter where a portion of the wall is built it will prevent movement of anything that walks, crawls, or slivers,” said Brian Segee, staff attorney for Defenders of Wildlife, a Washington, D.C., based non-profit organization.

Defenders of Wildlife is currently fighting the constitutionality of the “Real ID Act,” which was passed by Congress in 2005 and authorizes the Department of Homeland Security to bypass all state and federal environmental regulations to build walls and fences.

“We’re trying to have a lawful process so there can be dialogue to these important processes,” said Segee. “It’s a flagrant abuse of power but at the same time Congress is at fault for giving him [DHS Secretary Michael Chertoff] that power to abuse.”

Rodriguez said fencing is needed as a deterrent and will not encompass the whole border, just selected areas around ports of entry.

“You need something near a port of entry to slow them down,” said Rodriguez. “You only have seconds or minutes to apprehend them.”

Defenders of Wildlife endorse a continuation of the vehicle barrier in addition to increased Border Patrol staffing and the creation of high-tech “virtual fences” that use radar and cameras to alert authorities to immigrant movement.

The pedestrian traffic itself has serious consequences. As much as 200 miles of unnatural paths are being established that are ruining desert growth, erosion patterns, and are creating marked paths for illegal immigrants.

Trash and human waste are being discarded along the desert as immigrants walk toward the United States. The desert area is so sensitive that these foreign materials are affecting soil, plant life, and water quality which the national park was established to protect.

|

A border patrol agent arrests a drug smuggler along the border (Photo by Gerald L. Nino, U.S. Customs and Border Protection). |

“When the walking gets hard, you put down the stuff you don’t need,” said Fisher.

Illegal traffic in the park is having a damaging effect on the well being of the park. Cars abandoned near the vehicle barrier have to be towed at tax payer expense and at the expense of the desert system below it. Fires are built to signal for help but can quickly spread along the dry desert. Migrants are carving their names or hometowns in cactuses which can cause severe damage.

“We don’t know what the long-term damage is,” said Fisher.

Visitors are feeling the effects of illegal immigration and drug smuggling. Warning signs are posted and 60 percent of the park has been closed to visitors due to migration. “Border Security” is a link on the Organ Pipe official park website that tells visitors about closed areas and safety tips.

“It’s a catch-22,” said Tantay. “We’re trying to protect the public but the superintendent is receiving complaints regarding the park’s closure. We don’t want to take a risk with the public or our staff.”

Scientists require protection details provided by park rangers to do their work in the back country.

As chief of Interpretation, Fisher deals with visitors and their image of the park.

“I think visitors are concerned because they see the media coverage of it,” said Fisher. “They say it is a dangerous place but don’t explain what the story was trying to do.”

Fisher believes the media have made the park seem more dangerous than it really is. She said it would be rare for a visitor to encounter any danger and that the tourist areas and the migrant routes are far away from each other. She also says, statistically speaking, that the park has a low crime rate.

Visitation to the park was 341,594 in 2007 up from 313,103 in 2006.

The park is named after the organ pipe cactus that is plentiful in the park and has pipes sticking out from the base that resemble a church organ.

“I would encourage people to come here and to learn about the American story of immigration,” said Fisher. “It’s not a historical story but a current story.”

Organ Pipe is not the only national park to feel the effects of a tightened border. Big Bend National Park, encompassing 245 miles along the Rio Grande, is seeing a much smaller, but steadily increasing, number of illegal entrances.

Currently there are about 100 arrests every month with the park recently moving to close remote border campsites as a preventative measure. There have been similar trash and fire issues with migrants at Big Bend.

“We’ve had the luxury of watching Arizona,” said Big Bend Chief Ranger Mark Spier. “They’ve gotten run over. As the borders tighten down, we feel they will come through here at Big Bend. The position we’re taking is around preparation, prevention and protection.”

Comments are Closed